❞دايساكو إيكيدا❝ المؤلِّف الياباني - المكتبة

- ❞دايساكو إيكيدا❝ المؤلِّف الياباني - المكتبة

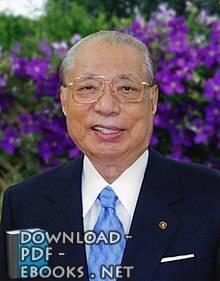

█ حصرياً جميع الاقتباسات من أعمال المؤلِّف ❞ دايساكو إيكيدا ❝ أقوال فقرات هامة مراجعات 2024 Daisaku Ikeda (池田 大作 Daisaku, born 2 January 1928) is a Buddhist philosopher, educator, author, and nuclear disarmament advocate [2][3][4] He has served as the third president then honorary of Soka Gakkai, largest Japan's new religious movements [5] founding Gakkai International (SGI), world's lay organization with approximately 12 million practitioners in 192 countries territories [6][7] Ikeda was Tokyo, Japan, 1928, to family seaweed farmers survived devastation World War II teenager, which he said left an indelible mark on his life fueled quest solve fundamental causes human conflict At age 19, began practicing Nichiren Buddhism joined youth group association, led lifelong work developing global peace movement SGI dozens institutions dedicated fostering peace, culture education [7]:3[8] Ikeda's vision for been described "borderless humanism that emphasizes free thinking personal development based respect all "[7]:26 In 1960s, worked reopen national relations China also establish network humanistic schools from kindergartens through university level, while beginning write what would become multi volume historical novel, The Human Revolution, about Gakkai's during mentor Josei Toda's tenure 1975, established International, throughout 1970s initiated series citizen diplomacy efforts international educational cultural exchanges Since 1980s, increasingly called elimination weapons [7]:23–25 By 2015, had published more than 50 dialogues scholars, activists leading world figures role president, visited 55 nations spoken subjects including environment, economics, women's rights, interfaith dialogue, disarmament, science Every year anniversary SGI's founding, 26 January, submits proposal United Nations [7]:11[9] Contents 1 Early background 2 Career 2 1 Youth leadership 2 2 Soka presidency 2 3 Soka founding 2 4 Resignation 5 Legacy 3 Accomplishments 3 1 Institutional engagement 3 2 Citizen diplomacy 3 3 Sino Japanese relations 4 Accolades 4 1 International awards 4 2 International honors 4 3 Academic honors 5 Personal life 6 Public image 7 Books 7 1 The Revolution 7 2 Selected works by Ikeda 8 References 9 External links 10 Soka presidency Early background Ikeda Ōta, 1928 four older brothers, two younger sister His parents later adopted children, total 10 children mid nineteenth century, successfully farmed nori, edible seaweed, Tokyo Bay By turn twentieth business producer nori However, after 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, family's enterprise ruins, time born, financially struggling [7] In 1937, full blown war erupted between Japan China, Ikeda's eldest brother, Kiichi, drafted into military service Within few years, three other elder brothers were well [10] 1942, overseas Asian theatres II, father, Nenokichi, fell ill bedridden years To help support family, at 14, working Niigata Steelworks munitions factory part wartime labor corps [11] In May 1945, home destroyed fire Allied air raid, forced move Omori area 1947, having received no word several — particular, mother informed government Kiichi killed action Burma (now Myanmar) [12][8] In August invited old friend attend discussion meeting It there met Toda, second As result this encounter, immediately regarded Toda spiritual mentor, became charter member group's division, stating influenced him "the profound compassion characterized each interactions "[13] Career Daisaku 19 Shortly end 1946, gained employment Shobundo Printing Company March 1948, graduated Toyo Trade School following month entered night school extension Taisei Gakuin (present day Fuji University) where majored political [8] During time, editor children's magazine Shonen Nihon (Boy's Life Japan), one companies [11][8] Over next 1948 1953, various owned enterprises, Shogakkan publishing company, Construction Trust credit Okura Shoji trading company [11][8] Youth leadership In 25, appointed leaders year, director public bureau, its chief staff [14]:85[11]:77 In April 1957, young members Osaka arrested allegedly distributing money, cigarettes candies campaign local electoral candidate (who member) detained jail weeks, charged overseeing these activities arrest came when candidates achieving success both levels With growing influence liberal grassroots movement, factions conservative establishment media attacks culminating After lengthy court case lasted until 1962, cleared charges [15] triumph over corrupt tyranny, galvanized [3] Soka presidency In 1960, death, Ikeda, 32 old, succeeded Soon after, travel build connections living abroad expand globally [16] expansion internationally was, words, "Toda's will future "[17] assumption presidency, "continued task begun [Soka founder] Tsunesaburo Makiguchi fusing ideas principles pragmatism elements doctrine "[2] While saw most dramatic growth under leadership, turned it considered largest, diverse association [6][18] reformed many organization's practices, aggressive conversion style (known shakubuku) known improved image, though sometimes still viewed suspicion [19][20][21][22][23] "By 1970s, leadership expanded active cultural, "[24] Soka founding On conference held Guam, representatives 51 created umbrella around This (SGI) took address assembly, encouraged dedicate themselves altruistic action, "Please devote yourselves planting seeds "[11]:128 The Guam symbolic gesture referencing Guam's history site some II's bloodiest battles, proximity Tinian Island, launching place atomic bombs dropped Hiroshima Nagasaki, [25] Resignation presidency From 1964 1990, title Sokoto (lay leader) among Shōshū adherents 1979, resigned (in accepting responsibility purported deviation doctrines accompanying priesthood [26] denomination associated since but relationship organizations often strained Hiroshi Hojo remained made [27] Ikeda excommunicated Shoshu 28 November 1991[8][28][29][30] 11 1992 [31][32] Following excommunication, describe their Buddhism's first Protestant [33] Legacy Ikeda's "globalized harnessed energy goals suited generations different cultures"[34] subsequently developed broad credited fostered ethos social strong spirit citizenship [35] thoughts "Buddhist humanism"[36] are situated within broader tradition East West dialogue search ideals [37] biography historian Arnold J Toynbee, William McNeill describes aim Toynbee "convergence West," positing pragmatic significance be realized "flourishing Western world" [38] Goulah's research transformative language learning characterizes inspired refinement Makiguchi's philosophy approach engendering "world view dialogic resistance" responds limitations neoliberal [39] Accomplishments Central activities, whether they institutional level or private citizen, belief rooted our shared humanity, faith dignity intersect promote positive change society "[40]:296 humanism," mutual dignity, agency engage Institutional engagement Ikeda greets students University, 1990 Ikeda founded education, University America Aliso Viejo, California; kindergarten, primary secondary Korea, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Brazil Singapore; Victor Hugo House Literature, Île de France region France; Committee Artists Peace States; Min On Concert Association Japan; Art Museum Institute Oriental Philosophy offices France, Hong, India, Russia Kingdom; Center Peace, Learning, Dialogue States [41] Since partnered Rabbi Abraham Cooper Simon Wiesenthal Center, Jewish rights organization, combat anti Semitism 2001 interview, stated "getting nowhere reaching out only partners we found us bring concerns people If you ask me who best is, 'gets it,' actually visitor Tolerance " Their friendship joint Holocaust exhibition Courage Remember, seen 1994 2007 version exhibit opened focusing bravery Anne Frank Chiune Sugihara [11][42] Ikeda original proponent Earth Charter Initiative, co Mikhail Gorbachev, included details annual proposals 1997 supported production exhibitions Seeds Change 2002 traveled 27 Hope 2010, correlating related documentary film, A Quiet donated programs [43][44] Since 26, 1983, submitted Nations, addressing such areas building gender equality empowerment women, UN reform universal civilization [45] abolishing special session General Assembly 1978, 1982 1988 built 1957 declaration condemning mass destruction "an absolute evil threatens people's right existence "[46] Citizen diplomacy Ikeda's academics contributions diplomatic intercultural ties countries, broadly peoples [47][48][49] politicians, have increased awareness humanitarian facilitated deeper relationships, generated sponsored issues environment [50][51] Countries President blue) outside red) Academic researchers suggested body literature chronicling 7,000 dialogues[52] provides readers model and, scholarly view, represents "a current interculturalism "[53][54][55][56] In 1970, times Austrian politician philosopher Richard von Coudenhove Kalergi, early pioneer European Union discussions [57] Between 1971 1974, conducted multiple London major topics meetings book Choose [58] French novelist Minister Cultural Affairs Andre Malraux [59] In September Soviet Premier Alexei Kosygin agreed saying "We must abandon very idea meaningless stop preparing prepare instead can produce food armaments asked "What your basic ideology?" replied, "I believe – underlying basis said, high regard those values We need realize them here "[60][61]:415[62] The located Cambridge, USA In Henry Kissinger, Secretary State, "urge escalation tensions "[4] same Kurt Waldheim presented petition containing signatures 10,000,000 calling abolition organized groups longtime [63] Ikeda's Nelson Mandela 1990s apartheid lectures, traveling exhibit, student exchange [64] Sino relations Ikeda visits Chinese Zhou Enlai Sino brutalities waged militarists [65] art, dance music academic [64] normalizing citing 1968 drew condemnation interest others [66][67] entrusted ensuring "Sino continue come "[68] Since continued Association, People's Friendship Foreign Countries [69][70] 1984 visit Communist Party Leader Hu Yaobang Deng Yingchao, observers estimated moved sentiment closer cultivation helped strengthen state [71] Accolades International awards During Turin Book Fair hosted event concluding 2018 five FIRMA Faiths Tune festival religion, Italy, jury award "for commitment interreligious "[72] Other awards include: Australia: Gold Medal Justice Sydney Foundation (2009)[73][74] Gandhi Prize Social Responsibility (2014)[75] China: Literary Award Understanding Literature Writersʼ (2003)[76] India: Tagore (1997)[77] Jamnalal Bajaj Outstanding Contribution Promotion Gandhian Values Outside India Individuals Indian Citizens (2005)[78] Indology Field Indic Research Wisdom (2011)[79] Macedonia: Humanism (Macedonian: НА СВЕТСКАТА НАГРАДА ЗА ХУМАНИЗАМ) Ohrid Academy (2007)[80] Philippines: Rizal (1998)[81] Golden Heart Knights (2012) [82] Gusi Prize[83] Russia: Order Russian Federation (2008)[84] Singapore: Wee Kim (2017)[85] Nations: (1983)[86][87][88] States: Rosa Parks Humanitarian (1993)[87] Education Transformation Project, Wellesley College (2001)[87] International honors In 1999, Martin Luther King Jr Chapel Morehouse Atlanta honored creation Ethics Reconciliation 2001, titled Gandhi, King, Ikeda: Legacy Building showcases activism Mahatma Jr, Also Lawrence Carter, ordained Baptist minister dean Atlanta, Community Builders way extolling individuals whose actions transcend philosophical boundaries 2015 bestowed upon Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen [89][90][91] Reflecting pool Ecological Park center Londrina, Brazil In 2000, city naming 300 acre nature reserve name Dr open land, waterways, fauna wildlife protected Brazil's Federal Conservation Law [92] In 2014, City Chicago named section Wabash Avenue downtown "Daisaku Way," Council measure passing unanimously, 49 0 [93] The Representatives individual states Georgia, Missouri, Illinois passed resolutions honoring dedication "who entire promoting deep conviction humanity Missouri praised value "education prerequisites true respected "[94][95][96][97][98] The Club Rome member,[99] 760 citizenships cities municipalities [7] At Day Poets February 2016, initiative launched Mohammed bin Rashid Award, along Kholoud Al Mulla UAE, K Satchidanandan Farouq Gouda Egypt [100] presenting honors, Shaikh Nahyan Mubarak reinforcing poetry, general, plays important spreading message world," echoing sentiments Hamad Shaibani, chair Award's board trustees, cited poets "promoting hope solidarity "[101] Academic Massachusetts Boston doctorate marking 300th honor receipt 1975 Moscow State [102] appreciation Boston, "The honors I accepted behalf recognition multifaceted redouble my "[103] Number Country Institution Title conferred Place date Personal life Ikeda lives wife, Kaneko (née Shiraki), whom married 3 1952 couple sons, Hiromasa (vice Gakkai),[157] Shirohisa (died 1984),[158] Takahiro [159] Public image American Civil Rights chose her favorite photograph image 1993 She explained: I can't think moment [Ikeda] meeting, us, me, too concern ahead century calm spirit, humble man, man great enlightenment hour talked challenges concerning Our serve anyone So because making [160] An article Daily News Analysis natural successor leader "[161] Chairman India's Studies, Professor N Radhakrishnan, hailed "one thinkers "[162] In 1984, British journalist commentator Polly invitation According Peter Popham, writing architecture culture, "was hoping tighten connection himself Toynbee's famous grandfather, prophet rise "[163] Toynbeee wrote she never "anyone exudes aura power Mr Ikeda" “felt drawn endorsing "[164][165] Guardian wished grandfather not endorsed Life: Dialogue, [165] In 1995, Michelle Magee critical San Francisco Chronicle accused "heavy handed fund raising proselytizing, intimidating foes trying grab "[166] quoted Takashi Shokei, professor Meisei hungry intends take control make religion " In 1996, Los Angeles Times writer Teresa Watanabe "puzzle conflicting perceptions," interview expressing vastly differing opinions him, ranging democrat," learning" teacher," despot," threat democracy" "Japan's powerful reported "Japanese tabloid coverage affected blurred lines fact, imagination reality "Nevertheless, question spreads goodwill transforms stereotypes "[167] In 2003, Dean College, reformer, stating: "Controversy inevitable partner greatness No order detractors, did exception Controversy camouflages intense resistance entrenched authority conceding status privilege Insults morally weak; slander tool spiritually bereft testament noble (Gandhi, Ikeda) respective societies "[89][168] Books Ikeda prolific writer, activist interpreter [169] interests photography, philosophy, poetry reflected essay collections political, discusses, topics: sanctity life,[170] responsibility, sustainable progress The 1976 publication Japanese, Nijusseiki e taiga) record correspondences West"[171] contemporary perennial condition Study History translated lecture tours periodical articles social, moral popularity expat's letter back: agree thing life, opposition militarism "[172] another responded: "Mr personality dynamic characters controversial My own feeling sympathy "[173] 2012, twenty six languages [174] In English newspaper, Times, carrying periodic essays peacebuilding, [178] 15 bilingual "Embracing Future "[179] The Revolution Ikeda's novel Revolution (Ningen Kakumei), serialized daily Seikyo Shimbun book's edition foreword written English, Chinese, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Korean Dutch sold seven millions copies worldwide [180] preface author "novelized "[181]:vii author's official website "historical [that] portrays rebirth post era last "[182] 2004 edition, narrative edited line recent developments Buddhism, hoped "such revisions better appreciate "[181]:x Selected IkedaArchived (PDF) 4 December 2013 Retrieved (26 2006) "A New Era People: Forging Global Network Robust (2006 Proposal)" 16 2017 Jupp, James C; Espinosa Dulanto, Miryam (2017) "Beyond US Centered Multicultural Foundations Race" Journal 19 (2): 33 McNeill, (1989) Toynbee: Life ❰ له مجموعة الإنجازات والمؤلفات أبرزها أجل السلام (شعر) ❱

Ikeda was born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1928, to a family of seaweed farmers. He survived the devastation of World War II as a teenager, which he said left an indelible mark on his life and fueled his quest to solve the fundamental causes of human conflict. At age 19, Ikeda began practicing Nichiren Buddhism and joined a youth group of the Soka Gakkai Buddhist association, which led to his lifelong work developing the global peace movement of SGI and founding dozens of institutions dedicated to fostering peace, culture and education.[7]:3[8]

Ikeda's vision for the SGI has been described as a "borderless Buddhist humanism that emphasizes free thinking and personal development based on respect for all life."[7]:26 In the 1960s, Ikeda worked to reopen Japan's national relations with China and also to establish the Soka education network of humanistic schools from kindergartens through university level, while beginning to write what would become his multi-volume historical novel, The Human Revolution, about the Soka Gakkai's development during his mentor Josei Toda's tenure. In 1975, he established the Soka Gakkai International, and throughout the 1970s initiated a series of citizen diplomacy efforts through international educational and cultural exchanges for peace. Since the 1980s, he has increasingly called for the elimination of nuclear weapons.[7]:23–25

By 2015, Ikeda had published more than 50 dialogues with scholars, peace activists and leading world figures. In his role as SGI president, Ikeda has visited 55 nations and spoken on subjects including peace, environment, economics, women's rights, interfaith dialogue, nuclear disarmament, and Buddhism and science. Every year on the anniversary of the SGI's founding, 26 January, Ikeda submits a peace proposal to the United Nations.[7]:11[9]

Contents

1 Early life and background

2 Career

2.1 Youth leadership

2.2 Soka Gakkai presidency

2.3 Soka Gakkai International founding

2.4 Resignation from Soka Gakkai presidency

2.5 Legacy

3 Accomplishments

3.1 Institutional engagement

3.2 Citizen diplomacy

3.3 Sino-Japanese relations

4 Accolades

4.1 International awards

4.2 International honors

4.3 Academic honors

5 Personal life

6 Public image

7 Books

7.1 The Human Revolution

7.2 Selected works by Ikeda

8 References

9 External links

10 Soka Gakkai presidency

Early life and background

Ikeda was born in Ōta, Tokyo, Japan, on 2 January 1928. Ikeda had four older brothers, two younger brothers, and a younger sister. His parents later adopted two more children, for a total of 10 children. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the Ikeda family had successfully farmed nori, edible seaweed, in Tokyo Bay. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Ikeda family business was the largest producer of nori in Tokyo. However, after the devastation of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, the family's enterprise was left in ruins, and by the time Ikeda was born, his family was financially struggling.[7]

In 1937, full-blown war erupted between Japan and China, and Ikeda's eldest brother, Kiichi, was drafted into military service. Within a few years, Ikeda's three other elder brothers were drafted as well.[10] In 1942, while all of his older brothers were overseas in the Asian theatres of World War II, Ikeda's father, Nenokichi, fell ill and was bedridden for two years. To help support his family, at the age of 14, Ikeda began working in the Niigata Steelworks munitions factory as part of Japan's wartime youth labor corps.[11]

In May 1945, Ikeda's home was destroyed by fire during an Allied air raid, and his family was forced to move to the Omori area of Tokyo. In May 1947, after having received no word from his eldest brother, Kiichi, for several years, the Ikeda family — in particular, his mother — was informed by the Japanese government that Kiichi had been killed in action in Burma (now Myanmar).[12][8]

In August 1947, at the age of 19, Ikeda was invited by an old friend to attend a Buddhist discussion meeting. It was there that he met Josei Toda, the second president of Japan's Soka Gakkai Buddhist organization. As a result of this encounter, Ikeda immediately began practicing Nichiren Buddhism and joined the Soka Gakkai. He regarded Toda as his spiritual mentor, and became a charter member of the group's youth division, later stating that Toda influenced him through "the profound compassion that characterized each of his interactions."[13]

Career

Daisaku Ikeda at age 19

Shortly after the end of World War II, in January 1946, Ikeda gained employment with the Shobundo Printing Company in Tokyo. In March 1948, Ikeda graduated from Toyo Trade School and the following month entered the night school extension of Taisei Gakuin (present-day Tokyo Fuji University) where he majored in political science.[8] During this time, he worked as an editor of the children's magazine Shonen Nihon (Boy's Life Japan), which was published by one of Josei Toda's companies.[11][8] Over the next several years, between 1948 and 1953, Ikeda worked for various Toda-owned enterprises, including the Nihon Shogakkan publishing company, the Tokyo Construction Trust credit association, and the Okura Shoji trading company.[11][8]

Youth leadership

In 1953, at the age of 25, Ikeda was appointed as one of the Soka Gakkai's youth leaders. The following year, he was appointed as director of the Soka Gakkai's public relations bureau, and later became its chief of staff.[14]:85[11]:77

In April 1957, a group of young Soka Gakkai members in Osaka were arrested for allegedly distributing money, cigarettes and candies to support the political campaign of a local electoral candidate (who was also a Soka Gakkai member). Ikeda was later arrested and detained in jail for two weeks, charged with allegedly overseeing these activities. Ikeda's arrest came at a time when Soka Gakkai Buddhist candidates were achieving success at both national and local levels. With the growing influence of this liberal grassroots movement, factions of the conservative political establishment initiated a series of media attacks on the Soka Gakkai, culminating in Ikeda's arrest. After a lengthy court case that lasted until 1962, Ikeda was cleared of all charges.[15] The Soka Gakkai characterized this as a triumph over corrupt tyranny, which galvanized its movement.[3]

Soka Gakkai presidency

In May 1960, two years after Toda's death, Ikeda, then 32 years old, succeeded him as president of the Soka Gakkai. Soon after, Ikeda began to travel overseas to build connections between Soka Gakkai members living abroad and expand the movement globally.[16] The expansion of the Soka Gakkai movement internationally was, in Ikeda's words, "Toda's will for the future."[17] With his assumption of the Soka Gakkai presidency, Ikeda "continued the task begun by [Soka Gakkai founder] Tsunesaburo Makiguchi of fusing the ideas and principles of educational pragmatism with the elements of Buddhist doctrine."[2]

While the Soka Gakkai saw its most dramatic growth after World War II under Toda's leadership, Ikeda led the international growth of the Soka Gakkai and turned it into what is considered the largest, most diverse international lay Buddhist association in the world.[6][18] He reformed many of the organization's practices, including the aggressive conversion style (known as shakubuku) for which the group had become known in Japan, and improved the organization's public image, though it was sometimes still viewed with suspicion in Japan.[19][20][21][22][23] "By the 1970s, Ikeda's leadership had expanded the Soka Gakkai into an international lay Buddhist movement increasingly active in peace, cultural, and educational activities."[24]

Soka Gakkai International founding

On 26 January 1975, a world peace conference was held in Guam, where Soka Gakkai representatives from 51 countries created an umbrella organization for the growing network of members around the world. This became the Soka Gakkai International (SGI). Ikeda took a leading role in the global organization's development and became the founding president of the SGI. In his address to the assembly, Ikeda encouraged the representatives to dedicate themselves to altruistic action, stating "Please devote yourselves to planting seeds of peace throughout the world."[11]:128

The SGI was created in part as a new international peace movement, and its founding meeting was held in Guam in a symbolic gesture referencing Guam's history as the site of some of World War II's bloodiest battles, and proximity to Tinian Island, launching place of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.[25]

Resignation from Soka Gakkai presidency

From 1964 to 1990, Ikeda held the title of Sokoto (lay leader) among Nichiren Shōshū adherents. In 1979, Ikeda resigned as president of the Soka Gakkai (in Japan), accepting responsibility for the organization's purported deviation from Nichiren Shōshū doctrines and accompanying conflict with its priesthood.[26] Nichiren Shōshū was the Buddhist denomination with which the Soka Gakkai had been associated since its founding, but the relationship between the two organizations was often strained. Hiroshi Hojo succeeded Ikeda as Soka Gakkai president, and Ikeda remained president of the Soka Gakkai International. Ikeda was also made honorary president of the Soka Gakkai in Japan.[27]

Ikeda and the Soka Gakkai were excommunicated by Nichiren Shoshu on 28 November 1991[8][28][29][30] and on 11 August 1992.[31][32] Following the group's excommunication, Soka Gakkai members began to describe their group as Buddhism's first Protestant movement.[33]

Legacy

Ikeda's leadership "globalized the Soka Gakkai and harnessed its energy to goals that suited new generations in different cultures"[34] and subsequently developed the SGI into a broad-based grassroots peace movement around the world. Ikeda is credited with having fostered among SGI members an ethos of social responsibility and a strong spirit of global citizenship.[35] Ikeda's thoughts and work on a "Buddhist-based humanism"[36] are situated within a broader tradition of East-West dialogue in search of humanistic ideals.[37] In his biography of historian Arnold J. Toynbee, William McNeill describes the aim of the Toynbee-Ikeda dialogues as a "convergence of East and West," positing the pragmatic significance of which would be realized by the "flourishing in the Western world" of the Soka Gakkai organization.[38] Goulah's research into transformative world language learning characterizes Ikeda's Buddhist-inspired refinement of Makiguchi's Soka education philosophy as an approach engendering a "world view of dialogic resistance" that responds to the limitations of a neoliberal world view of education.[39]

Accomplishments

Central to Ikeda's activities, whether they be on an institutional level or as a private citizen, is his belief in "Buddhist principles ... rooted in our shared humanity, ... where faith and human dignity intersect to promote positive change in society."[40]:296 His view of a "Buddhist humanism," the fostering of mutual respect and dignity, emphasizes human agency to engage in dialogue.

Institutional engagement

Ikeda greets international students at Soka University, March 1990

Ikeda has founded many global institutions for the development of peace, culture and education, including Soka University in Tokyo, Japan, and Soka University of America in Aliso Viejo, California; Soka kindergarten, primary and secondary schools in Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Brazil and Singapore; the Victor Hugo House of Literature, in the Île-de-France region of France; the International Committee of Artists for Peace in the United States; the Min-On Concert Association in Japan; the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum in Japan; the Institute of Oriental Philosophy in Japan with offices in France, Hong Hong, India, Russia and the United Kingdom; the Toda Peace Institute in Japan and the United States; and the Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue in the United States.[41]

Since 1990, Ikeda has partnered with Rabbi Abraham Cooper and the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a Jewish human rights organization, to combat anti-Semitism in Japan. In a 2001 interview, Rabbi Cooper stated he was "getting nowhere after reaching out to the Japanese media about anti-Semitism in Japan. The only partners we found to help us bring our concerns to the Japanese public were people from Soka University under the leadership of Daisaku Ikeda. If you ask me who our best friend in Japan is, who 'gets it,' it is Ikeda. He was actually our first visitor to the Museum of Tolerance." Their friendship led to the joint development of a Japanese-language Holocaust exhibition The Courage to Remember, which was seen by more than two million people in Japan between 1994 and 2007. In 2015, a new version of the exhibit opened in Tokyo focusing on the bravery of Anne Frank and Chiune Sugihara.[11][42]

Ikeda was an original proponent of the Earth Charter Initiative, co-founded by Mikhail Gorbachev, and Ikeda has included details of the Charter in many of his annual peace proposals since 1997. The SGI has supported the Earth Charter with production of global exhibitions including Seeds of Change in 2002 that traveled to 27 nations and Seeds of Hope in 2010, correlating with the Earth Charter-related documentary film, A Quiet Revolution, which the SGI has donated to schools and educational programs around the world.[43][44]

Since January 26, 1983, Ikeda has submitted annual peace proposals to the United Nations, addressing such areas as building a culture of peace, gender equality in education, empowerment of women, UN reform and universal human rights with a view on global civilization.[45] Ikeda's proposals for nuclear disarmament and abolishing nuclear weapons submitted to the special session of the UN General Assembly in 1978, 1982 and 1988 built on his mentor Josei Toda's 1957 declaration condemning such weapons of mass destruction as "an absolute evil that threatens the people's right of existence."[46]

Citizen diplomacy

Ikeda's work has been described by academics as citizen diplomacy for his contributions to diplomatic as well as intercultural ties between Japan and other countries, and more broadly among all peoples of the world.[47][48][49] Ikeda's dialogues with scholars, politicians, and cultural figures have increased awareness and support of humanitarian and peace activities, have facilitated deeper international relationships, and generated support for SGI-sponsored work on global issues including the environment and nuclear disarmament.[50][51]

Countries visited by SGI President Ikeda (in blue) outside of Japan (in red)

Academic researchers have suggested the body of literature chronicling Ikeda's diplomatic efforts and his more than 7,000 international dialogues[52] provides readers with a personal education and model of citizen diplomacy and, from a scholarly view, represents "a new current in interculturalism and educational philosophy."[53][54][55][56]

In 1970, Ikeda met several times with Austrian-Japanese politician and philosopher Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, an early pioneer of the European Union. Their discussions included East-West relations and the future of peace work.[57] Between 1971 and 1974, Ikeda conducted multiple dialogues with Arnold J. Toynbee in London and Tokyo. The major topics of their meetings were published as the book Choose Life.[58] In 1974, Ikeda conducted a dialogue with French novelist and Minister of Cultural Affairs Andre Malraux.[59]

In September 1974, Ikeda visited the Soviet Union and met with Premier Alexei Kosygin. During their dialogue, Kosygin agreed with Ikeda, saying "We must abandon the very idea of war. It is meaningless. If we stop preparing for war and prepare instead for peace, we can produce food instead of armaments." He then asked Ikeda, "What is your basic ideology?" Ikeda replied, "I believe in peace, culture and education – the underlying basis of which is humanism." Kosygin said, "I have a high regard for those values. We need to realize them here in the Soviet Union as well."[60][61]:415[62]

The Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue located in Cambridge, USA

In January 1975, Ikeda met with Henry Kissinger, the United States Secretary of State, to "urge the de-escalation of nuclear tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union."[4] The same month Ikeda met with Secretary-General of the United Nations Kurt Waldheim. Ikeda presented Waldheim with a petition containing the signatures of 10,000,000 people calling for total nuclear abolition. The petition was organized by youth groups of the Soka Gakkai International and was inspired by Ikeda's longtime anti-nuclear efforts.[63]

Ikeda's meetings with Nelson Mandela in the 1990s led to a series of SGI-sponsored anti-apartheid lectures, a traveling exhibit, and multiple student exchange programs at the university level.[64]

Sino-Japanese relations

Ikeda made several visits to China and met with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1974, though Sino-Japanese tensions remained over the brutalities of war waged by the Japanese militarists.[65] The visits led to the establishment of cultural exchanges of art, dance and music between China and Japan and opened academic exchanges between Chinese educational institutions and Soka University.[64] Chinese media describe Ikeda as an early proponent of normalizing diplomatic relations between China and Japan in the 1970s, citing his 1968 proposal that drew condemnation by some and the interest of others including Zhou Enlai.[66][67] It was said that Zhou Enlai entrusted Ikeda with ensuring that "Sino-Japanese friendship would continue for generations to come."[68]

Since 1975, cultural exchanges have continued between the Min-On Concert Association, founded by Ikeda, and institutions including the Chinese People's Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries.[69][70] After Ikeda's 1984 visit to China and meetings with public figures including Chinese Communist Party Leader Hu Yaobang and Deng Yingchao, academic observers estimated that Ikeda's 1968 proposal moved Japanese public sentiment to support closer diplomatic ties with China and his cultivation of educational and cultural ties helped strengthen state relations.[71]

Accolades

International awards

During a Turin Book Fair-hosted event concluding the 2018 five-day FIRMA-Faiths in Tune festival of religion, music and art, held in 2018 for the first time in Italy, an international jury presented a FIRMA award to Daisaku Ikeda "for his lifelong commitment to interreligious dialogue."[72] Other international awards received by Ikeda include:

Australia: Gold Medal for Peace with Justice from the Sydney Peace Foundation (2009)[73][74]

Australia: Gandhi International Prize for Social Responsibility (2014)[75]

China: International Literary Award for Understanding and Friendship from the China Literature Foundation and Chinese Writersʼ Association (2003)[76]

India: Tagore Peace Award (1997)[77]

India: Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Outstanding Contribution in Promotion of Gandhian Values Outside India by Individuals other than Indian Citizens (2005)[78]

India: Indology Award for Outstanding Contribution in the Field of Indic Research and Oriental Wisdom (2011)[79]

Macedonia: World Prize for Humanism (Macedonian: НА СВЕТСКАТА НАГРАДА ЗА ХУМАНИЗАМ) from the Ohrid Academy of Humanism (2007)[80]

Philippines: Rizal International Peace Award (1998)[81]

Philippines: Golden Heart Award from the Knights of Rizal (2012) [82]

Philippines: Gusi Peace Prize[83]

Russia: Order of Friendship of the Russian Federation (2008)[84]

Singapore: Wee Kim Wee Gold Award (2017)[85]

United Nations: United Nations Peace Medal (1983)[86][87][88]

United States: Rosa Parks Humanitarian Award (1993)[87]

United States: International Tolerance Award from the Simon Wiesenthal Center (1993)[87]

United States: Education as Transformation Award from the Education as Transformation Project, Wellesley College (2001)[87]

International honors

In 1999, the Martin Luther King Jr. Chapel at Morehouse College in Atlanta honored Ikeda with the creation of the Gandhi King Ikeda Institute for Ethics and Reconciliation. In 2001, a traveling exhibition was created titled Gandhi, King, Ikeda: A Legacy of Building Peace that showcases the peace activism of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr, and Daisaku Ikeda. Also in 2001, Lawrence Carter, an ordained Baptist minister and a dean at Morehouse College in Atlanta, initiated the annual Gandhi, King, Ikeda Community Builders Prize as a way of extolling individuals whose actions for peace transcend cultural, national and philosophical boundaries. The 2015 Gandhi King Ikeda award was bestowed upon Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen.[89][90][91]

Reflecting pool at the Daisaku Ikeda Ecological Park visitor center in Londrina, Brazil

In 2000, the city of Londrina, Brazil honored Ikeda by naming a 300-acre nature reserve in his name. The Dr. Daisaku Ikeda Ecological Park is open to the public and its land, waterways, fauna and wildlife are protected by Brazil's Federal Conservation Law.[92]

In 2014, the City of Chicago named a section of Wabash Avenue in downtown Chicago "Daisaku Ikeda Way," with the Chicago City Council measure passing unanimously, 49 to 0.[93]

The United States House of Representatives and individual states including Georgia, Missouri, and Illinois have passed resolutions honoring the service and dedication of Daisaku Ikeda as one "who has dedicated his entire life to building peace and promoting human rights through education and cultural exchange with deep conviction in the shared humanity of our entire global family." The state of Missouri praised Ikeda and his value of "education and culture as the prerequisites for the creation of true peace in which the dignity and fundamental rights of all people are respected."[94][95][96][97][98]

The Club of Rome has named Ikeda an honorary member,[99] and Ikeda has received more than 760 honorary citizenships from cities and municipalities around the world.[7]

At the International Day for Poets of Peace in February 2016, an initiative launched by the Mohammed bin Rashid World Peace Award, Daisaku Ikeda from Japan along with Kholoud Al Mulla from the UAE, K. Satchidanandan from India and Farouq Gouda from Egypt were named International Poets of Peace.[100] In presenting the honors, Shaikh Nahyan bin Mubarak Al Nahyan described the initiative as reinforcing "the idea that poetry, and literature in general, are a universal language that plays an important role in spreading the message of peace in the world," echoing the sentiments of Dr Hamad Al Shaikh Al Shaibani, chair of the World Peace Award's board of trustees, who cited the role of poets in "promoting a culture of hope and solidarity."[101]

Academic honors

In November 2010, the University of Massachusetts Boston bestowed an honorary doctorate upon Ikeda, marking the 300th academic honor he had received since receipt of his first honorary doctorate in 1975 from Moscow State University.[102] In his message of appreciation to the University of Massachusetts Boston, Ikeda said "The academic honors I have accepted have all been on behalf of the members of SGI around the world. This is recognition of their multifaceted contributions. As a private citizen, I will redouble my efforts to promote peace, cultural exchange and education."[103]

Number Country Institution Title conferred Place and date

Personal life

Ikeda lives in Tokyo with his wife, Kaneko Ikeda (née Kaneko Shiraki), whom he married on 3 May 1952. The couple had three sons, Hiromasa (vice president of Soka Gakkai),[157] Shirohisa (died 1984),[158] and Takahiro.[159]

Public image

American Civil Rights pioneer Rosa Parks chose as her favorite photograph an image from her first meeting with Ikeda in 1993. She explained:

I can't think of a more important moment in my life ... [Ikeda] said this meeting, between the two of us, was very special for him. It was for me, too. In his concern for human rights, Dr. Ikeda is ahead of many people in this century. He is a calm spirit, a humble man, a man of great spiritual enlightenment. We met for about an hour and talked about my life and challenges concerning the youth in our countries ... Our meeting can serve as a model for anyone. So the photograph of our first meeting is very important because it is history in the making.[160]

An article in Daily News and Analysis called him "the natural successor to Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. as a global spiritual leader."[161] The Chairman of India's Council of Gandhian Studies, Professor N. Radhakrishnan, has hailed Ikeda as "one of the most profound thinkers of our time."[162]

In 1984, British journalist and political commentator Polly Toynbee visited Ikeda at the invitation of the SGI. According to Peter Popham, writing about Tokyo architecture and culture, Ikeda "was hoping to tighten the public connection between himself and Polly Toynbee's famous grandfather, Arnold Toynbee, the prophet of the rise of the East."[163] Polly Toynbeee wrote that she had never met "anyone who exudes such an aura of absolute power as Mr. Ikeda" and others she had talked to “felt they had been drawn into endorsing [Ikeda]."[164][165] In The Guardian in May 1984, she wrote that she wished that her grandfather had not endorsed Choose Life: A Dialogue, his dialogue with Ikeda.[165]

In 1995, Michelle Magee wrote a critical article in the San Francisco Chronicle in which she stated that the Soka Gakkai in Japan had been accused of "heavy-handed fund raising and proselytizing, as well as intimidating its foes and trying to grab political power."[166] The article quoted Takashi Shokei, a professor at Meisei University, who called Ikeda "a power-hungry individual who intends to take control of the government and make Soka Gakkai the national religion."

In 1996, Los Angeles Times writer Teresa Watanabe described Ikeda as a "puzzle of conflicting perceptions," with her interview subjects expressing vastly differing opinions of him, ranging from "a democrat," "a man of deep learning" and "an inspired teacher," to "a despot," "a threat to democracy" and "Japan's most powerful man." Watanabe reported that "Japanese tabloid coverage has affected his public image and blurred the lines between suspicion and fact, imagination and reality ..." concluding that "Nevertheless, there is no question that Ikeda spreads goodwill – and transforms stereotypes."[167]

In 2003, Dr. Lawrence Carter, Dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. Chapel at Morehouse College, praised Ikeda as a Japanese social reformer, stating: "Controversy is an inevitable partner of greatness. No one who challenges the established order is free of it. Gandhi had his detractors, as did Dr. King, and Dr. Ikeda is no exception. Controversy camouflages the intense resistance of entrenched authority to conceding their special status and privilege. Insults are the weapons of the morally weak; slander is the tool of the spiritually bereft. Controversy is testament to the noble work of these three individuals (Gandhi, King and Ikeda) in their respective societies."[89][168]

Books

Ikeda is a prolific writer, peace activist and interpreter of Nichiren Buddhism.[169] His interests in photography, art, philosophy, poetry and music are reflected in his published works. In his essay collections and dialogues with political, cultural, and educational figures he discusses, among other topics: the transformative value of religion, the universal sanctity of life,[170] social responsibility, and sustainable progress and development.

The 1976 publication of Choose Life: A Dialogue (in Japanese, Nijusseiki e no taiga) is the published record of dialogues and correspondences that began in 1971 between Ikeda and British historian Arnold J. Toynbee about the "convergence of East and West"[171] on contemporary as well as perennial topics ranging from the human condition to the role of religion and the future of human civilization. Toynbee's 12-volume A Study of History had been translated into Japanese, which along with his lecture tours and periodical articles about social, moral and religious issues gained him popularity in Japan. To an expat's letter critical of Toynbee's association with Ikeda and Soka Gakkai, Toynbee wrote back: "I agree with Soka Gakkai on religion as the most important thing in human life, and on opposition to militarism and war."[172] To another letter critical of Ikeda, Toynbee responded: "Mr. Ikeda's personality is strong and dynamic and such characters are often controversial. My own feeling for Mr. Ikeda is one of great respect and sympathy."[173] As of 2012, the book had been translated and published in twenty-six languages.[174]

In 2003, Japan's largest English-language newspaper, The Japan Times, began carrying periodic essays by Ikeda on global issues including peacebuilding, nuclear disarmament, and compassion.[178] As of 2015, The Japan Times had published 26 essays by Ikeda, 15 of which were also published in a bilingual Japanese-English book titled "Embracing the Future."[179]

The Human Revolution

Ikeda's most well-known publication is the novel The Human Revolution (Ningen Kakumei), which was serialized in the Soka Gakkai's daily newspaper, the Seikyo Shimbun. The book's original English-edition foreword was written by British philosopher and historian Arnold J. Toynbee. The Human Revolution has been translated into English, Chinese, French, German, Spanish, Portuguese, Korean and Dutch and has sold over seven millions copies worldwide.[180] In the preface to The Human Revolution, the author describes the book as a "novelized biography of my mentor, Josei Toda."[181]:vii The author's official website describes the book as an "historical novel [that] portrays the development of the Soka Gakkai in Japan, from its rebirth in the post-World War II era to the last years of its second president, Josei Toda."[182] In the preface to the 2004 edition, the author stated the narrative was edited to bring it in line with recent developments in the history of Nichiren Buddhism, and that he hoped "such revisions will help readers to better appreciate the original message of the book."[181]:x

Selected works by IkedaArchived from the original (PDF) on 4 December 2013. Retrieved 4 December 2013..

Ikeda, Daisaku (26 January 2006). "A New Era of the People: Forging a Global Network of Robust Individuals (2006 Peace Proposal)". Soka Gakkai International. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

Jupp, James C; Espinosa-Dulanto, Miryam (2017). "Beyond US-Centered Multicultural Foundations on Race". International Journal of Multicultural Education. 19 (2): 33. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

McNeill, William (1989). Arnold J. Toynbee: A Life

❰ له مجموعة من الإنجازات والمؤلفات أبرزها ❞ من أجل السلام (شعر) ❝ ❱

Daisaku Ikeda (池田 大作 Ikeda Daisaku, born 2 January 1928) is a Buddhist philosopher, educator, author, and nuclear disarmamentadvocate.[2][3][4] He has served as the third president and then honorary president of the Soka Gakkai, the largest of Japan's new religious movements.[5] Ikeda is the founding president of the Soka Gakkai International (SGI), the world's largest Buddhist lay organization with approximately 12 million practitioners in 192 countries and territories.[6][7]

Ikeda was born in Tokyo, Japan, in 1928, to a family of seaweed farmers. He survived the devastation of World War II as a teenager, which he said left an indelible mark on his life and fueled his quest to solve the fundamental causes of human conflict. At age 19, Ikeda began practicing Nichiren Buddhism and joined a youth group of the Soka Gakkai Buddhist association, which led to his lifelong work developing the global peace movement of SGI and founding dozens of institutions dedicated to fostering peace, culture and education.[7]:3[8]

Ikeda's vision for the SGI has been described as a "borderless Buddhist humanism that emphasizes free thinking and personal development based on respect for all life."[7]:26 In the 1960s, Ikeda worked to reopen Japan's national relations with China and also to establish the Soka education network of humanistic schools from kindergartens through university level, while beginning to write what would become his multi-volume historical novel, The Human Revolution, about the Soka Gakkai's development during his mentor Josei Toda's tenure. In 1975, he established the Soka Gakkai International, and throughout the 1970s initiated a series of citizen diplomacy efforts through international educational and cultural exchanges for peace. Since the 1980s, he has increasingly called for the elimination of nuclear weapons.[7]:23–25

By 2015, Ikeda had published more than 50 dialogues with scholars, peace activists and leading world figures. In his role as SGI president, Ikeda has visited 55 nations and spoken on subjects including peace, environment, economics, women's rights, interfaith dialogue, nuclear disarmament, and Buddhism and science. Every year on the anniversary of the SGI's founding, 26 January, Ikeda submits a peace proposal to the United Nations.[7]:11[9]

Contents

- 1Early life and background

- 2Career

- 3Accomplishments

- 4Accolades

- 5Personal life

- 6Public image

- 7Books

- 8References

- 9External links

- 10Soka Gakkai presidency

Early life and background[edit]

Ikeda was born in Ōta, Tokyo, Japan, on 2 January 1928. Ikeda had four older brothers, two younger brothers, and a younger sister. His parents later adopted two more children, for a total of 10 children. Since the mid-nineteenth century, the Ikeda family had successfully farmed nori, edible seaweed, in Tokyo Bay. By the turn of the twentieth century, the Ikeda family business was the largest producer of nori in Tokyo. However, after the devastation of the 1923 Great Kantō earthquake, the family's enterprise was left in ruins, and by the time Ikeda was born, his family was financially struggling.[7]

In 1937, full-blown war erupted between Japan and China, and Ikeda's eldest brother, Kiichi, was drafted into military service. Within a few years, Ikeda's three other elder brothers were drafted as well.[10] In 1942, while all of his older brothers were overseas in the Asian theatres of World War II, Ikeda's father, Nenokichi, fell ill and was bedridden for two years. To help support his family, at the age of 14, Ikeda began working in the Niigata Steelworks munitions factory as part of Japan's wartime youth labor corps.[11]

In May 1945, Ikeda's home was destroyed by fire during an Allied air raid, and his family was forced to move to the Omori area of Tokyo. In May 1947, after having received no word from his eldest brother, Kiichi, for several years, the Ikeda family — in particular, his mother — was informed by the Japanese government that Kiichi had been killed in action in Burma (now Myanmar).[12][8]

In August 1947, at the age of 19, Ikeda was invited by an old friend to attend a Buddhist discussion meeting. It was there that he met Josei Toda, the second president of Japan's Soka Gakkai Buddhist organization. As a result of this encounter, Ikeda immediately began practicing Nichiren Buddhism and joined the Soka Gakkai. He regarded Toda as his spiritual mentor, and became a charter member of the group's youth division, later stating that Toda influenced him through "the profound compassion that characterized each of his interactions."[13]

Career[edit]

Daisaku Ikeda at age 19

Shortly after the end of World War II, in January 1946, Ikeda gained employment with the Shobundo Printing Company in Tokyo. In March 1948, Ikeda graduated from Toyo Trade School and the following month entered the night school extension of Taisei Gakuin (present-day Tokyo Fuji University) where he majored in political science.[8] During this time, he worked as an editor of the children's magazine Shonen Nihon (Boy's Life Japan), which was published by one of Josei Toda's companies.[11][8] Over the next several years, between 1948 and 1953, Ikeda worked for various Toda-owned enterprises, including the Nihon Shogakkan publishing company, the Tokyo Construction Trust credit association, and the Okura Shoji trading company.[11][8]

Youth leadership[edit]

In 1953, at the age of 25, Ikeda was appointed as one of the Soka Gakkai's youth leaders. The following year, he was appointed as director of the Soka Gakkai's public relations bureau, and later became its chief of staff.[14]:85[11]:77

In April 1957, a group of young Soka Gakkai members in Osaka were arrested for allegedly distributing money, cigarettes and candies to support the political campaign of a local electoral candidate (who was also a Soka Gakkai member). Ikeda was later arrested and detained in jail for two weeks, charged with allegedly overseeing these activities. Ikeda's arrest came at a time when Soka Gakkai Buddhist candidates were achieving success at both national and local levels. With the growing influence of this liberal grassroots movement, factions of the conservative political establishment initiated a series of media attacks on the Soka Gakkai, culminating in Ikeda's arrest. After a lengthy court case that lasted until 1962, Ikeda was cleared of all charges.[15] The Soka Gakkai characterized this as a triumph over corrupt tyranny, which galvanized its movement.[3]

Soka Gakkai presidency[edit]

In May 1960, two years after Toda's death, Ikeda, then 32 years old, succeeded him as president of the Soka Gakkai. Soon after, Ikeda began to travel overseas to build connections between Soka Gakkai members living abroad and expand the movement globally.[16] The expansion of the Soka Gakkai movement internationally was, in Ikeda's words, "Toda's will for the future."[17] With his assumption of the Soka Gakkai presidency, Ikeda "continued the task begun by [Soka Gakkai founder] Tsunesaburo Makiguchi of fusing the ideas and principles of educational pragmatism with the elements of Buddhist doctrine."[2]

While the Soka Gakkai saw its most dramatic growth after World War II under Toda's leadership, Ikeda led the international growth of the Soka Gakkai and turned it into what is considered the largest, most diverse international lay Buddhist association in the world.[6][18] He reformed many of the organization's practices, including the aggressive conversion style (known as shakubuku) for which the group had become known in Japan, and improved the organization's public image, though it was sometimes still viewed with suspicion in Japan.[19][20][21][22][23] "By the 1970s, Ikeda's leadership had expanded the Soka Gakkai into an international lay Buddhist movement increasingly active in peace, cultural, and educational activities."[24]

Soka Gakkai International founding[edit]

On 26 January 1975, a world peace conference was held in Guam, where Soka Gakkai representatives from 51 countries created an umbrella organization for the growing network of members around the world. This became the Soka Gakkai International (SGI). Ikeda took a leading role in the global organization's development and became the founding president of the SGI. In his address to the assembly, Ikeda encouraged the representatives to dedicate themselves to altruistic action, stating "Please devote yourselves to planting seeds of peace throughout the world."[11]:128

The SGI was created in part as a new international peace movement, and its founding meeting was held in Guam in a symbolic gesture referencing Guam's history as the site of some of World War II's bloodiest battles, and proximity to Tinian Island, launching place of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan.[25]

Resignation from Soka Gakkai presidency[edit]

From 1964 to 1990, Ikeda held the title of Sokoto (lay leader) among Nichiren Shōshū adherents. In 1979, Ikeda resigned as president of the Soka Gakkai (in Japan), accepting responsibility for the organization's purported deviation from Nichiren Shōshū doctrines and accompanying conflict with its priesthood.[26] Nichiren Shōshū was the Buddhist denomination with which the Soka Gakkai had been associated since its founding, but the relationship between the two organizations was often strained. Hiroshi Hojo succeeded Ikeda as Soka Gakkai president, and Ikeda remained president of the Soka Gakkai International. Ikeda was also made honorary president of the Soka Gakkai in Japan.[27]

Ikeda and the Soka Gakkai were excommunicated by Nichiren Shoshu on 28 November 1991[8][28][29][30] and on 11 August 1992.[31][32] Following the group's excommunication, Soka Gakkai members began to describe their group as Buddhism's first Protestant movement.[33]

Legacy[edit]

Ikeda's leadership "globalized the Soka Gakkai and harnessed its energy to goals that suited new generations in different cultures"[34] and subsequently developed the SGI into a broad-based grassroots peace movement around the world. Ikeda is credited with having fostered among SGI members an ethos of social responsibility and a strong spirit of global citizenship.[35] Ikeda's thoughts and work on a "Buddhist-based humanism"[36] are situated within a broader tradition of East-West dialogue in search of humanistic ideals.[37] In his biography of historian Arnold J. Toynbee, William McNeill describes the aim of the Toynbee-Ikeda dialogues as a "convergence of East and West," positing the pragmatic significance of which would be realized by the "flourishing in the Western world" of the Soka Gakkai organization.[38] Goulah's research into transformative world language learning characterizes Ikeda's Buddhist-inspired refinement of Makiguchi's Soka education philosophy as an approach engendering a "world view of dialogic resistance" that responds to the limitations of a neoliberal world view of education.[39]

Accomplishments[edit]

Central to Ikeda's activities, whether they be on an institutional level or as a private citizen, is his belief in "Buddhist principles ... rooted in our shared humanity, ... where faith and human dignity intersect to promote positive change in society."[40]:296 His view of a "Buddhist humanism," the fostering of mutual respect and dignity, emphasizes human agency to engage in dialogue.

Institutional engagement[edit]

Ikeda greets international students at Soka University, March 1990

Ikeda has founded many global institutions for the development of peace, culture and education, including Soka University in Tokyo, Japan, and Soka University of America in Aliso Viejo, California; Soka kindergarten, primary and secondary schools in Japan, Korea, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Brazil and Singapore; the Victor Hugo House of Literature, in the Île-de-France region of France; the International Committee of Artists for Peace in the United States; the Min-On Concert Association in Japan; the Tokyo Fuji Art Museum in Japan; the Institute of Oriental Philosophy in Japan with offices in France, Hong Hong, India, Russia and the United Kingdom; the Toda Peace Institute in Japan and the United States; and the Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue in the United States.[41]

Since 1990, Ikeda has partnered with Rabbi Abraham Cooper and the Simon Wiesenthal Center, a Jewish human rights organization, to combat anti-Semitism in Japan. In a 2001 interview, Rabbi Cooper stated he was "getting nowhere after reaching out to the Japanese media about anti-Semitism in Japan. The only partners we found to help us bring our concerns to the Japanese public were people from Soka University under the leadership of Daisaku Ikeda. If you ask me who our best friend in Japan is, who 'gets it,' it is Ikeda. He was actually our first visitor to the Museum of Tolerance." Their friendship led to the joint development of a Japanese-language Holocaust exhibition The Courage to Remember, which was seen by more than two million people in Japan between 1994 and 2007. In 2015, a new version of the exhibit opened in Tokyo focusing on the bravery of Anne Frank and Chiune Sugihara.[11][42]

Ikeda was an original proponent of the Earth Charter Initiative, co-founded by Mikhail Gorbachev, and Ikeda has included details of the Charter in many of his annual peace proposals since 1997. The SGI has supported the Earth Charter with production of global exhibitions including Seeds of Change in 2002 that traveled to 27 nations and Seeds of Hope in 2010, correlating with the Earth Charter-related documentary film, A Quiet Revolution, which the SGI has donated to schools and educational programs around the world.[43][44]

Since January 26, 1983, Ikeda has submitted annual peace proposals to the United Nations, addressing such areas as building a culture of peace, gender equality in education, empowerment of women, UN reform and universal human rights with a view on global civilization.[45] Ikeda's proposals for nuclear disarmament and abolishing nuclear weapons submitted to the special session of the UN General Assembly in 1978, 1982 and 1988 built on his mentor Josei Toda's 1957 declaration condemning such weapons of mass destruction as "an absolute evil that threatens the people's right of existence."[46]

Citizen diplomacy[edit]

Ikeda's work has been described by academics as citizen diplomacy for his contributions to diplomatic as well as intercultural ties between Japan and other countries, and more broadly among all peoples of the world.[47][48][49] Ikeda's dialogues with scholars, politicians, and cultural figures have increased awareness and support of humanitarian and peace activities, have facilitated deeper international relationships, and generated support for SGI-sponsored work on global issues including the environment and nuclear disarmament.[50][51]

Countries visited by SGI President Ikeda (in blue) outside of Japan (in red)

Academic researchers have suggested the body of literature chronicling Ikeda's diplomatic efforts and his more than 7,000 international dialogues[52] provides readers with a personal education and model of citizen diplomacy and, from a scholarly view, represents "a new current in interculturalism and educational philosophy."[53][54][55][56]

In 1970, Ikeda met several times with Austrian-Japanese politician and philosopher Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi, an early pioneer of the European Union. Their discussions included East-West relations and the future of peace work.[57] Between 1971 and 1974, Ikeda conducted multiple dialogues with Arnold J. Toynbee in London and Tokyo. The major topics of their meetings were published as the book Choose Life.[58] In 1974, Ikeda conducted a dialogue with French novelist and Minister of Cultural Affairs Andre Malraux.[59]

In September 1974, Ikeda visited the Soviet Union and met with Premier Alexei Kosygin. During their dialogue, Kosygin agreed with Ikeda, saying "We must abandon the very idea of war. It is meaningless. If we stop preparing for war and prepare instead for peace, we can produce food instead of armaments." He then asked Ikeda, "What is your basic ideology?" Ikeda replied, "I believe in peace, culture and education – the underlying basis of which is humanism." Kosygin said, "I have a high regard for those values. We need to realize them here in the Soviet Union as well."[60][61]:415[62]

The Ikeda Center for Peace, Learning, and Dialogue located in Cambridge, USA

In January 1975, Ikeda met with Henry Kissinger, the United States Secretary of State, to "urge the de-escalation of nuclear tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union."[4] The same month Ikeda met with Secretary-General of the United Nations Kurt Waldheim. Ikeda presented Waldheim with a petition containing the signatures of 10,000,000 people calling for total nuclear abolition. The petition was organized by youth groups of the Soka Gakkai International and was inspired by Ikeda's longtime anti-nuclear efforts.[63]

Ikeda's meetings with Nelson Mandela in the 1990s led to a series of SGI-sponsored anti-apartheid lectures, a traveling exhibit, and multiple student exchange programs at the university level.[64]

Sino-Japanese relations[edit]

Ikeda made several visits to China and met with Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai in 1974, though Sino-Japanese tensions remained over the brutalities of war waged by the Japanese militarists.[65] The visits led to the establishment of cultural exchanges of art, dance and music between China and Japan and opened academic exchanges between Chinese educational institutions and Soka University.[64] Chinese media describe Ikeda as an early proponent of normalizing diplomatic relations between China and Japan in the 1970s, citing his 1968 proposal that drew condemnation by some and the interest of others including Zhou Enlai.[66][67] It was said that Zhou Enlai entrusted Ikeda with ensuring that "Sino-Japanese friendship would continue for generations to come."[68]

Since 1975, cultural exchanges have continued between the Min-On Concert Association, founded by Ikeda, and institutions including the Chinese People's Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries.[69][70] After Ikeda's 1984 visit to China and meetings with public figures including Chinese Communist Party Leader Hu Yaobang and Deng Yingchao, academic observers estimated that Ikeda's 1968 proposal moved Japanese public sentiment to support closer diplomatic ties with China and his cultivation of educational and cultural ties helped strengthen state relations.[71]

Accolades[edit]

International awards[edit]

During a Turin Book Fair-hosted event concluding the 2018 five-day FIRMA-Faiths in Tune festival of religion, music and art, held in 2018 for the first time in Italy, an international jury presented a FIRMA award to Daisaku Ikeda "for his lifelong commitment to interreligious dialogue."[72] Other international awards received by Ikeda include:

Australia: Gold Medal for Peace with Justice from the Sydney Peace Foundation (2009)[73][74]

Australia: Gold Medal for Peace with Justice from the Sydney Peace Foundation (2009)[73][74] Australia: Gandhi International Prize for Social Responsibility (2014)[75]

Australia: Gandhi International Prize for Social Responsibility (2014)[75] China: International Literary Award for Understanding and Friendship from the China Literature Foundation and Chinese Writersʼ Association (2003)[76]

China: International Literary Award for Understanding and Friendship from the China Literature Foundation and Chinese Writersʼ Association (2003)[76] India: Tagore Peace Award (1997)[77]

India: Tagore Peace Award (1997)[77] India: Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Outstanding Contribution in Promotion of Gandhian Values Outside India by Individuals other than Indian Citizens (2005)[78]

India: Jamnalal Bajaj Award for Outstanding Contribution in Promotion of Gandhian Values Outside India by Individuals other than Indian Citizens (2005)[78] India: Indology Award for Outstanding Contribution in the Field of Indic Research and Oriental Wisdom (2011)[79]

India: Indology Award for Outstanding Contribution in the Field of Indic Research and Oriental Wisdom (2011)[79] Macedonia: World Prize for Humanism (Macedonian: НА СВЕТСКАТА НАГРАДА ЗА ХУМАНИЗАМ) from the Ohrid Academy of Humanism (2007)[80]

Macedonia: World Prize for Humanism (Macedonian: НА СВЕТСКАТА НАГРАДА ЗА ХУМАНИЗАМ) from the Ohrid Academy of Humanism (2007)[80] Philippines: Rizal International Peace Award (1998)[81]

Philippines: Rizal International Peace Award (1998)[81] Philippines: Golden Heart Award from the Knights of Rizal (2012) [82]

Philippines: Golden Heart Award from the Knights of Rizal (2012) [82] Philippines: Gusi Peace Prize[83]

Philippines: Gusi Peace Prize[83] Russia: Order of Friendship of the Russian Federation (2008)[84]

Russia: Order of Friendship of the Russian Federation (2008)[84] Singapore: Wee Kim Wee Gold Award (2017)[85]

Singapore: Wee Kim Wee Gold Award (2017)[85] United Nations: United Nations Peace Medal (1983)[86][87][88]

United Nations: United Nations Peace Medal (1983)[86][87][88] United States: Rosa Parks Humanitarian Award (1993)[87]

United States: Rosa Parks Humanitarian Award (1993)[87] United States: International Tolerance Award from the Simon Wiesenthal Center (1993)[87]

United States: International Tolerance Award from the Simon Wiesenthal Center (1993)[87] United States: Education as Transformation Award from the Education as Transformation Project, Wellesley College (2001)[87]

United States: Education as Transformation Award from the Education as Transformation Project, Wellesley College (2001)[87]

International honors[edit]

In 1999, the Martin Luther King Jr. Chapel at Morehouse College in Atlanta honored Ikeda with the creation of the Gandhi King Ikeda Institute for Ethics and Reconciliation. In 2001, a traveling exhibition was created titled Gandhi, King, Ikeda: A Legacy of Building Peace that showcases the peace activism of Mahatma Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr, and Daisaku Ikeda. Also in 2001, Lawrence Carter, an ordained Baptist minister and a dean at Morehouse College in Atlanta, initiated the annual Gandhi, King, Ikeda Community Builders Prize as a way of extolling individuals whose actions for peace transcend cultural, national and philosophical boundaries. The 2015 Gandhi King Ikeda award was bestowed upon Islamic scholar Fethullah Gülen.[89][90][91]

Reflecting pool at the Daisaku Ikeda Ecological Park visitor center in Londrina, Brazil

In 2000, the city of Londrina, Brazil honored Ikeda by naming a 300-acre nature reserve in his name. The Dr. Daisaku Ikeda Ecological Park is open to the public and its land, waterways, fauna and wildlife are protected by Brazil's Federal Conservation Law.[92]

In 2014, the City of Chicago named a section of Wabash Avenue in downtown Chicago "Daisaku Ikeda Way," with the Chicago City Council measure passing unanimously, 49 to 0.[93]

The United States House of Representatives and individual states including Georgia, Missouri, and Illinois have passed resolutions honoring the service and dedication of Daisaku Ikeda as one "who has dedicated his entire life to building peace and promoting human rights through education and cultural exchange with deep conviction in the shared humanity of our entire global family." The state of Missouri praised Ikeda and his value of "education and culture as the prerequisites for the creation of true peace in which the dignity and fundamental rights of all people are respected."[94][95][96][97][98]

The Club of Rome has named Ikeda an honorary member,[99] and Ikeda has received more than 760 honorary citizenships from cities and municipalities around the world.[7]

At the International Day for Poets of Peace in February 2016, an initiative launched by the Mohammed bin Rashid World Peace Award, Daisaku Ikeda from Japan along with Kholoud Al Mulla from the UAE, K. Satchidanandan from India and Farouq Gouda from Egypt were named International Poets of Peace.[100] In presenting the honors, Shaikh Nahyan bin Mubarak Al Nahyan described the initiative as reinforcing "the idea that poetry, and literature in general, are a universal language that plays an important role in spreading the message of peace in the world," echoing the sentiments of Dr Hamad Al Shaikh Al Shaibani, chair of the World Peace Award's board of trustees, who cited the role of poets in "promoting a culture of hope and solidarity."[101]

Academic honors[edit]

In November 2010, the University of Massachusetts Boston bestowed an honorary doctorate upon Ikeda, marking the 300th academic honor he had received since receipt of his first honorary doctorate in 1975 from Moscow State University.[102] In his message of appreciation to the University of Massachusetts Boston, Ikeda said "The academic honors I have accepted have all been on behalf of the members of SGI around the world. This is recognition of their multifaceted contributions. As a private citizen, I will redouble my efforts to promote peace, cultural exchange and education."[103]

| showNumber | Country | Institution | Title conferred | Place and date |

|---|

Personal life[edit]

Ikeda lives in Tokyo with his wife, Kaneko Ikeda (née Kaneko Shiraki), whom he married on 3 May 1952. The couple had three sons, Hiromasa (vice president of Soka Gakkai),[157]Shirohisa (died 1984),[158] and Takahiro.[159]

Public image[edit]

American Civil Rights pioneer Rosa Parks chose as her favorite photograph an image from her first meeting with Ikeda in 1993. She explained:

I can't think of a more important moment in my life ... [Ikeda] said this meeting, between the two of us, was very special for him. It was for me, too. In his concern for human rights, Dr. Ikeda is ahead of many people in this century. He is a calm spirit, a humble man, a man of great spiritual enlightenment. We met for about an hour and talked about my life and challenges concerning the youth in our countries ... Our meeting can serve as a model for anyone. So the photograph of our first meeting is very important because it is history in the making.[160]

An article in Daily News and Analysis called him "the natural successor to Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King, Jr. as a global spiritual leader."[161] The Chairman of India's Council of Gandhian Studies, Professor N. Radhakrishnan, has hailed Ikeda as "one of the most profound thinkers of our time."[162]

In 1984, British journalist and political commentator Polly Toynbee visited Ikeda at the invitation of the SGI. According to Peter Popham, writing about Tokyo architecture and culture, Ikeda "was hoping to tighten the public connection between himself and Polly Toynbee's famous grandfather, Arnold Toynbee, the prophet of the rise of the East."[163] Polly Toynbeee wrote that she had never met "anyone who exudes such an aura of absolute power as Mr. Ikeda" and others she had talked to “felt they had been drawn into endorsing [Ikeda]."[164][165] In The Guardian in May 1984, she wrote that she wished that her grandfather had not endorsed Choose Life: A Dialogue, his dialogue with Ikeda.[165]

In 1995, Michelle Magee wrote a critical article in the San Francisco Chronicle in which she stated that the Soka Gakkai in Japan had been accused of "heavy-handed fund raising and proselytizing, as well as intimidating its foes and trying to grab political power."[166] The article quoted Takashi Shokei, a professor at Meisei University, who called Ikeda "a power-hungry individual who intends to take control of the government and make Soka Gakkai the national religion."

In 1996, Los Angeles Times writer Teresa Watanabe described Ikeda as a "puzzle of conflicting perceptions," with her interview subjects expressing vastly differing opinions of him, ranging from "a democrat," "a man of deep learning" and "an inspired teacher," to "a despot," "a threat to democracy" and "Japan's most powerful man." Watanabe reported that "Japanese tabloid coverage has affected his public image and blurred the lines between suspicion and fact, imagination and reality ..." concluding that "Nevertheless, there is no question that Ikeda spreads goodwill – and transforms stereotypes."[167]

In 2003, Dr. Lawrence Carter, Dean of the Martin Luther King Jr. Chapel at Morehouse College, praised Ikeda as a Japanese social reformer, stating: "Controversy is an inevitable partner of greatness. No one who challenges the established order is free of it. Gandhi had his detractors, as did Dr. King, and Dr. Ikeda is no exception. Controversy camouflages the intense resistance of entrenched authority to conceding their special status and privilege. Insults are the weapons of the morally weak; slander is the tool of the spiritually bereft. Controversy is testament to the noble work of these three individuals (Gandhi, King and Ikeda) in their respective societies."[89][168]

Books[edit]

Ikeda is a prolific writer, peace activist and interpreter of Nichiren Buddhism.[169] His interests in photography, art, philosophy, poetry and music are reflected in his published works. In his essay collections and dialogues with political, cultural, and educational figures he discusses, among other topics: the transformative value of religion, the universal sanctity of life,[170] social responsibility, and sustainable progress and development.

The 1976 publication of Choose Life: A Dialogue (in Japanese, Nijusseiki e no taiga) is the published record of dialogues and correspondences that began in 1971 between Ikeda and British historian Arnold J. Toynbee about the "convergence of East and West"[171] on contemporary as well as perennial topics ranging from the human condition to the role of religion and the future of human civilization. Toynbee's 12-volume A Study of History had been translated into Japanese, which along with his lecture tours and periodical articles about social, moral and religious issues gained him popularity in Japan. To an expat's letter critical of Toynbee's association with Ikeda and Soka Gakkai, Toynbee wrote back: "I agree with Soka Gakkai on religion as the most important thing in human life, and on opposition to militarism and war."[172] To another letter critical of Ikeda, Toynbee responded: "Mr. Ikeda's personality is strong and dynamic and such characters are often controversial. My own feeling for Mr. Ikeda is one of great respect and sympathy."[173] As of 2012, the book had been translated and published in twenty-six languages.[174]

Ikeda's children's stories are "widely read and acclaimed," according to The Hindu, which reported that an anime series of 14 of the stories was to be shown on the National Geographic Channel.[175][176] In the Philippines, DVD sets of 17 of the animated stories were donated by Anak TV to a large school, as part of a nationwide literacy effort.[177]

In 2003, Japan's largest English-language newspaper, The Japan Times, began carrying periodic essays by Ikeda on global issues including peacebuilding, nuclear disarmament, and compassion.[178] As of 2015, The Japan Times had published 26 essays by Ikeda, 15 of which were also published in a bilingual Japanese-English book titled "Embracing the Future."[179]

The Human Revolution[edit]